第11届2017第六届中国国际老龄产业博览会观众预登记通道,将于2017年5月开启,

敬请期待。如有问题请与我们联系,

电话: +86 (0)20 8989 9605/8989 9600,

邮箱:CRCinfo@polycn.com

Industry News 2014-03-13

Making a move to a senior housing community may be infused with excitement, indecision, questions about identity, and physical exhaustion. Many of these same thoughts and feelings are provoked during any relocation to a new home at any stage of life. The difference lies in the congregate style of housing and the availability of onsite medical and assistive support in the new home. Some residents describe the move as an opportunity for friendships and optimizing life without the hassles of managing a home, while others struggle to adapt to the change (Carroll and Qualls, 2013).

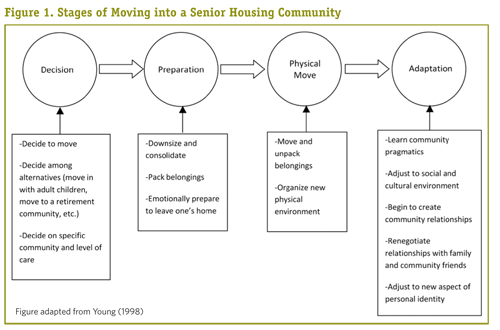

A move into elder housing is a process involving several stages (see Figure 1, below), including choosing among alternative facilities, a significant downsizing of possessions, moving to the new environment, and adapting to the new environment (Young, 1998). Also, the initial move opens up the possibility of additional future moves—relocations within the same community to different levels of care, depending upon need. Any of these moves can create challenges as well as opportunities. A particular new challenge is navigating the social world within the elder housing setting, while maintaining external relationships.

Deciding to Move and Determining Level of Care

Relocation to a retirement community can be precipitated by a variety of factors and initially may be resisted. Sometimes, the move is made because of the older adult’s frailty (36 percent) or because of the spouse’s frailty (7 percent) (Bernard et al., 2007). Within couples, one spouse often extends significant care for the other while delaying relocation. When they move, the level of independence or care is based on the partner with higher care needs (Kemp, 2011). Reasons for making the move into a retirement community and choosing a level of care vary for each couple or individual who chooses to move. These varied rationales result in retirement communities populated by older adults with differing perspectives on the new environment.

Families are often involved in the decision to move, and may help choose the level of support needed by their loved one. The industry calls this process “placement,” and residents may feel powerless if they are placed into a certain level of care without having a say in the decision. Selecting the level of care is based on personal preference, health needs, monetary resources, and senior housing regulations (Morgan et al., 2006). Residents sometimes move into independent living at their own insistence, and then are faced with another move when they require a higher level of care (Morgan et al., 2006). Families sometimes encourage a level of care that is not yet required, which leads to frustration for the older adult and fosters unnecessary dependency.

Other families may insist on placement in independent living because they are in denial about the frailty of their loved one. Elder housing companies sometimes encourage older adults to move into a vacant apartment that lacks needed supports, to keep occupancy rates high. Inappropriate placement quickly becomes apparent to other residents and staff after move-in, resulting in extra time spent on care and monitoring of that resident to ensure their safety (Carroll and Qualls, 2012, 2013). If placed in a lower level of care than necessary, the older adult may be unsafe in his or her living environment and faced with an additional move to the appropriate level at a later date.

Great Expectations? Integrating into a New Community

The decision to move into a retirement community indicates that the older adult has chosen a new home and will anticipate eventually experiencing the comfort of home in that environment (Young, 1998). Older adults expect that moving into elder housing, especially to assisted living or memory care, will be the final move they make in life (Pitts, Krieger, and Nussbaum, 2005; Young, 1998). This leads to fears of mortality surfacing and may force the elder to put his or her life into a new perspective. Older adult housing administrators are tasked with providing an environment conducive to adapting and feeling at home, socially accepted, and supported.

Settling in

After deciding to move and choosing a level of housing, the older adult makes the move into a new home. Residents of elder housing describe the move as physically and emotionally challenging (Carroll and Qualls, 2013) but the move itself may be less challenging than is the settling in that follows (Young, 1998). Anticipating the unknown within the new community could be one reason many residents find the move exhausting. Within elder housing, an older adult not only moves into a new personal setting, but also must adjust to the practical aspects of the community, the social and cultural environment, and to a new piece of

personal identity (Young, 1998).

Socialization within the community

The social environment can require the greatest effort of all the adapting that’s done. Elder housing residents often report ambivalence about labeling other residents as friends, and yet fellow residents often self-identify within social circles upon questioning from researchers (Carroll and Qualls, 2013). Residents in senior housing make friends, but those friendships may be structured and defined differently than they would be in a community setting. New friendships within elder housing are characterized by the frequent exchange of support and can be created within seven months of move-in (Shea, Thompson, and Blieszner, 1988). The support given and received by older adults in senior housing is most commonly expressive (giving and receiving advice, discussing problems) and is less frequently instrumental (help with personal care, physical assistance, and prompting) (Kaye and Monk, 1991).

Residents may develop expressive support and a sense of community by discussing common challenges. This is called “troubles talk” and thought to be one of the ways by which residents establish common ground and integrate socially into elder housing (Faircloth, 2001). Troubles talk could center on other residents or the senior housing community itself. Elder housing residents sometimes stray toward troubles talk by gossiping, which was observed by researchers completing assessments unrelated to community gossip (Carroll and Qualls, 2013). Gossip may be a means by which residents express their status in the social world of elder housing, and can reflect something shared between residents, who

may otherwise struggle to find commonalities.

Transitions and social links across levels of care

Many older adult campuses offer multiple levels of housing, such as independent patio homes, independent apartments, and assisted living, with the intent of helping individuals transition to more supportive services when necessary, while preserving continuity of place. However, friendships do not often follow those transitions, even if the move is to another floor or nearby building on the same campus and the friendships were solid prior to one of the older adults moving to a higher level of care (Shippee, 2009, 2012). The need for higher care represents the potential frailty of older age and creates fear of personal health declines (Williams and Warren, 2009). Although residents freely provide emotional support to one another, physical health becomes a friendship determinant and structures the capacity to give and receive emotional support.

Independent living residents in multi-level campuses are often at the top of the social hierarchy due to a common value of good physical and cognitive health (Shippee, 2009, 2012). If independent living residents begin to experience physical or cognitive health declines, they fear losing their relatively autonomous way of life in independent living. One strategy for ignoring the potential for future frailty and need for additional services is to avoid interaction with persons who live in those feared future residences such as assisted living or memory care.

Several residents of independent living described their reasoning for not including residents with dementia in social circles. The residents with dementia, they said, are not desirable social partners because he or she is “always repeating themselves” and “cannot follow conversations” (Carroll and Qualls, 2012). Physically or cognitively impaired residents risk social exclusion within the independent living community and may even separate themselves from others in anticipation of the differential treatment they may receive as a result of their health (Shippee, 2012).

Moving to a dementia care unit or skilled nursing facility is typically the final residential move for an individual with advanced memory loss. The transition to this setting can mean losing friendships from previous levels of care due to the aforementioned status hierarchy and resident fears (Shippee, 2009, 2012; Williams and Warren, 2009). At the same time, the new environment allows the opportunity to form new friendships. Researchers find that older adults with advanced dementia make friends and that those friendships possess similar traits to relationships between people without dementia (Saunders et al., 2011). Residents may use objects in the environment, abstract ideas, or other people as interactional topics. Within this level of care, staff should be aware that care routines and the creation of distractions can both help residents and risk intruding on the formation of friendships (Saunders et al., 2011).

The Role of Staff: Enabling New Connections

Staff members of elder housing are working in the home of the residents they serve, but are not employed by the resident. But residents’ relationships with staff often transcend the typical care provider and care recipient relationship. Staff can become important members of an older adult’s social support network. Residents of elder housing sometimes identify staff as part of their social networks as early as the first year of residency, likely due to the complex support that staff provides (Carroll and Qualls, 2013). When care levels change or a staff member leaves, it can cause residents to feel distress.

During a longitudinal study within a senior housing facility, residents expressed high concern when a staff member was asked to leave, and, in the eyes of the residents, simply “disappeared” (Carroll and Qualls, 2012, 2013). The balance of care provided by staff members should be given with mindfulness. Staff relationships with residents have obvious benefits as well as risks to the resident if that social support is lost without warning, or if a staff member demonstrates poor boundaries in managing the relationship (Phillips and Guo, 2011).

Staff can help create opportunities for residents to develop friendships, although residents’ personalities and social skills dictate what they do with those opportunities. Socializing (or not) within the elder housing environment is a resident’s choice; some residents may choose to spend time alone, which does not necessarily indicate poor adaptation (McKee, Harrison, and Lee, 1999). Mrs. M, an outgoing and sociable independent living resident, described her efforts to balance friendliness with personal boundaries by noting that she valued her time alone and wanted to interact with residents in the community without residents visiting her in her room each evening (Carroll and Qualls, 2013). Spending time alone may be part of how residents who are introverted by nature and value time alone adapt to their environment. Each resident’s well-being can be individually monitored to decipher maladaptive isolation from an adaptive personal choice. Depression and loneliness screens, engaging in focused conversations with residents, and formal and informal assessments of social support can help elder housing staff differentiate introversion from social isolation.

Connections to Outside Networks

An older adult’s social network external to the senior housing community tends to remain stable while fluctuating to accommodate adaptation over time (Antonucci and Akiyama, 1987). The social network an older adult maintains while in senior housing largely depends on the structure of the network over time and prior to the move. Those with solid support networks prior to a move will likely preserve those networks after the move and be more likely to successfully socially integrate into the new community (Miller, 1986).

Family relationships are particularly resilient to life changes and family members often feel obligated to help during times of change or struggle (Bedford and Blieszner, 1997; Rawlins, 1995). Those lacking solid support networks, particularly those with few family members, may struggle more than others with the adaptation process because of limited external support, and may benefit from additional support from facility staff.

When social support is lacking, people feel lonely. Following move-in, family members may be less accessible due to busyness in their own lives or the perceived segregation of the older adult within elder housing. Quality relationships within the social network (children, neighbors, and close friends) are closely connected to decreased feelings of loneliness (Mullins, 1990). Frequent contact with these key social network members is pertinent to the older adult’s wellbeing. Following a move to elder housing, frequent contact with neighbors within the facility, who have the potential to become close friends, may decrease loneliness (Mullins, 1990).

The Role of Staff Redux: Social Partners and Care Providers

The idea of moving has a different meaning when the new home is within an elder housing facility. Physically, a move into senior housing resembles other forms of relocation in which downsizing and adaptation are required, with the added factor of the immersion into a new social and cultural community within one’s immediate surroundings. Friendships between elder housing residents can be an essential source of emotional support during a new phase in the older adult’s life. Senior housing staff are positioned as both social partners and providers of care. Although residents’ relationships are rare across housing levels, senior housing staff has the ability to transcend those boundaries and maintain quality care and friendships across transitions to higher levels of care.

However, staff must be mindful of the temporary nature of their employment, which makes the social support they provide to residents potentially transient. For optimal wellbeing in senior housing, relationships with other residents and with people outside the facility are important. Powerful and complex processes are involved in forming and maintaining relationships in elder housing that warrant support by facilities, staff, residents, and long-term networks outside the facility.

Jocelyn Carroll, M.A., is a senior member engagement advocate at UnitedHealthcare. Sara Honn Qualls, Ph.D., is a professor of psychology at the University of Colorado Colorado Springs. She also serves as the Kraemer Family Professor of Aging Studies at the University and is director of the University’s Gerontology Center.

Editor’s Note: This article is taken from the Spring 2014 issue of ASA’s quarterly journal, Generations, an issue devoted to the topic “Relationships, Health, and Well-Being in Later Life.” ASA members receive Generations as a membership benefit; non-members may purchase subscriptions or single copies of issues at our online store. Full digital access to current and back issues of Generations is also available to ASA members and Generations subscribers at MetaPress.

References

Antonucci, T. C., and Akiyama, H. 1987. “Social Networks in Adult Life and a Preliminary Examination of the Convoy Model.” Journal of Gerontology 42(5): 519–27.

Bedford, V. H., and Blieszner, R. 1997. “Personal Relationships in Later-life Families.” In Duck, S., ed., Handbook of Personal Relationships: Theory, Research and Interventions (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Bernard, M., et al. 2007. “Housing and Care for Older People: Life in an English Purpose-built Retirement Village.” Ageing and Society 27(4): 555–78.

Carroll, J., and Qualls, S. H. 2012. “The Impact of Cognitive Impairment on Socialization within Senior Housing.” Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Coleman Institute for Cognitive Disabilities, Westminster, CO, November 2012.

Carroll, J., and Qualls, S. H. 2013. “Social Integration into Senior Housing and Associated Wellbeing.” Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Gerontological Society of America, New Orleans, LA, November 2013.

Faircloth, C. A. 2001. “ ‘Those People’ and Troubles Talk: Social Typing and Community Construction in Senior Public Housing.” Journal of Aging Studies 15(4): 333–50.

Kaye, L. W., and Monk, A. 1991. “Social Relations in Enriched Housing for the Aged: A Case Study.” Journal of Housing for the Elderly 9(1–3): 111–26.

Kemp, C. L. 2011. “Married Couples in Assisted Living: Adult Children’s Experiences Providing Support.” Journal of Family Issues 33(5): 639–61.

McKee, K. J., Harrison, G., and Lee, K. 1999. “Activity, Friendships and Well-being in Residential Settings for Older People.” Aging and Mental Health 3(2): 143–52.

Miller, S. J. 1986. “Relationships in Long-term-care Facilities.” Generations 10(4): 65–9.

Morgan, L. A., et al. 2006. “Two Lives in Transition: Agency and Context for Assisted Living Residents.” Journal of Aging Studies 20(2): 123–32.

Mullins, L. C. 1990. “The Influence of Depression, and Family and Friendship Relations, on Residents’ Loneliness in Congregate Housing.” The Gerontologist 30(3): 377–84.

Pitts, M. F. J., Krieger, J. L., and Nussbaum, J. 2005. “Finding the Right Place: Social Interaction and Life Transitions among the Elderly.” In Ray, E. B., ed., Health Communication in Practice: A Case Study Approach. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Phillips, L. R., and Guo, G. 2011. “Mistreatment in Assisted Living Facilities: Complaints, Substantiations, and Risk Factors.” The Gerontologist 51(3): 343–53.

Rawlins, W. K. 1995. “Friendships in Later Life.” In Nussbaum, J. F., and Coupland, J., eds., Handbook of Communication and Aging Research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Saunders, P. A., et al. 2011. “The Discourse of Friendship: Mediators of Communication among Dementia Residents in Long-term Care.” Dementia 11(3): 347–61.

Shea, L., Thompson, L., and Blieszner, R. 1988. “Resources in Older Adults’ Old and New Friendships.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 5(1): 83–96.

Shippee, T. P. 2009. “ ‘But I Am Not Moving’: Residents’ Perspectives on Transitions within a Continuing Care Retirement Community.” The Gerontologist 49(3): 418–27.

Shippee, T. P. 2012. “On the Edge: Balancing Health, Participation, and Autonomy to Maintain Active Independent Living in Two Retirement Facilities.” Journal of Aging Studies 26(1): 1–15.

Williams, K. N., and Warren, C. A. B. 2009. “Communication in Assisted Living.” Journal of Aging Studies 23(1): 24–36.

Young, H. M. 1998. “Moving to Congregate Housing: The Last Chosen Home.” Journal of Aging Studies 12(2): 149–65.

From: American Society on Aging

http://www.asaging.org/blog/moving-senior-housing-adapting-old-embracing-new

Date: November 26-28, 2026

Venue: PWTC Expo, Guangzhou

Barrier-free Living Rehabilitation equipments and therapy Daily necessities for the elderly Nursing aids Featured services for the aged Elderly care services Smart elderly care Health and wellness

Christina Lin

Tel: +86(0)20 8989 9651, 15820261270

Email: linjinqi@polycn.com